This week on the What is The Future for Cities? podcast, we found ourselves caught in the crossfire of one of the biggest debates in urban development: do we fix what we have, or do we start again?

We approached this question from two very different angles. First, we looked at the cold, hard numbers in our research debate, analysing a comparative study of the Radex Park Marywilska project in Warsaw in episode 393R. Then in episode 394I, we sat down with Harriet Shing MP, the Victorian Minister for Housing, Building, and Precincts, to understand the political and practical realities of making these decisions for a city of millions.

While we often hear about the environmental arguments, this week we stripped that away to look at the economics, the governance, and the human side of the equation.

Here are the five key lessons we took away.

1. The economic clash: capital savings vs market value

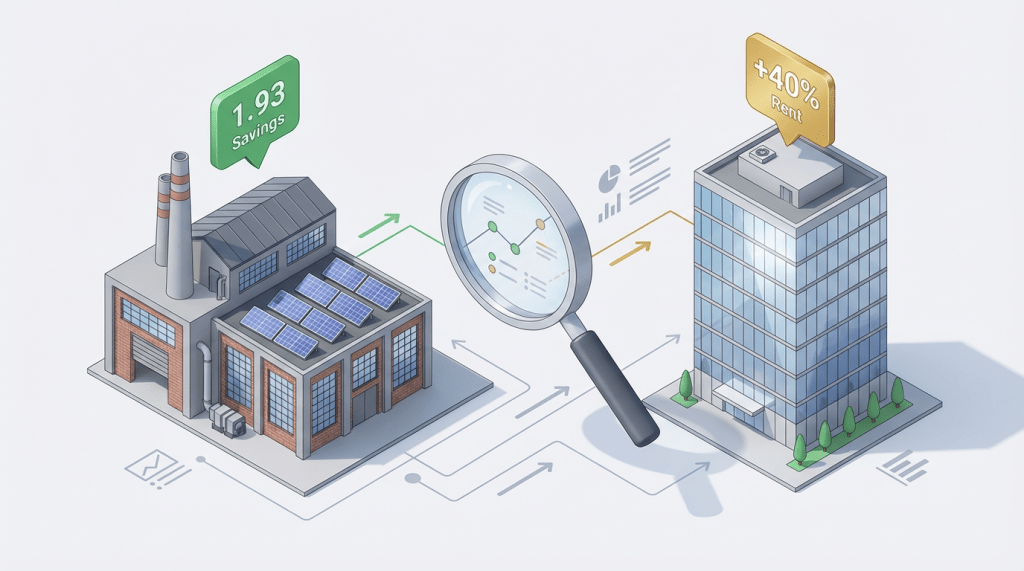

In episode 393R, we examined a fascinating piece of research that pitted adaptive reuse against demolition and new construction. The results challenged the assumption that “new is always more profitable.”

The study found that adaptive reuse – taking an old industrial site and repurposing it – was undeniably the champion of capital efficiency. The project achieved a “savings ratio” of 1.93. This means that for every single dollar (or Polish Zloty) invested in the project, it generated nearly double that in combined benefits. The direct cost savings were massive, slashing the upfront capital expenditure by nearly 57% compared to building from scratch.

However, there was a sting in the tail. While the retrofit saved money upfront, the hypothetical new build would have commanded a 40% higher rental premium over a 15-year period. The modern, purpose-built facility offered superior functionality that the market was willing to pay for – creating an 18 million PLN gap in potential gross revenue.

The lesson: It is a choice between business models. Do you want low risk and low upfront costs (retrofit), or are you willing to spend big now to secure a higher-value asset for the long term (new build)? There is no single “correct” economic answer; it depends on your appetite for risk and your timeline.

2. Why we can’t always just “fix it up”

It is easy to romanticise the idea of turning every old building into loft apartments. However, in episode 394, Minister Harriet Shing brought us back down to earth with a reality check on construction standards.

We discussed the future of Melbourne’s 44 social housing towers, built between the 1950s and 1970s. The Minister explained why retrofitting these specific structures is technically close to impossible. These buildings were constructed using a unique concrete slab method where the doorway widths and lift wells are set in stone – literally and figuratively.

The result? You cannot fit a stretcher into the lifts. The bathrooms are not disability accessible. The ceiling heights are too low for modern standards. To fix them would require such extensive intervention that it ceases to be a retrofit and becomes a rebuild in all but name.

The lesson: Adaptive reuse has hard physical limits. As the Minister noted, we have to look at this on a “case-by-case basis”. If saving a building means condemning residents to sub-standard living conditions – like the notorious “dog box” apartments of the past with no natural light or airflow – then preservation is not the right choice.

3. The delicate balance: regulation vs innovation

One of the most heated debates in urban planning is where the government should stop and the market should start. Does government “meddling” just drive up prices?

Harriet Shing argued that while the market drives delivery, a lack of a “referee” leads to failures—like builder collapses or the “dog box” apartments of the past . She emphasized that regulations, such as the new mandatory reserve price laws, are vital for consumer protection . However, the tension is real. Every new standard—from disability access to energy ratings—adds cost and complexity .

The lesson: It is a tightrope walk. Too little regulation leaves buyers exposed to “dodgy product,” but too much can stifle affordability. The goal isn’t to choose sides, but to find the guardrails that ensure quality without breaking the bank.

4. Infrastructure changes our “mental map” of the city

How do you define “Melbourne”? Is it just the Hoddle Grid? Or does it stretch to the bay, the north, and the outer east?

Harriet Shing spoke about how major infrastructure projects fundamentally rewrite the geography of a city. The Metro Tunnel, for example, isn’t just a train line; it is a tool that shrinks distance. By connecting Sunshine to Pakenham, it changes where people can feasibly live and work.

We are also seeing a shift from “radial” thinking (everything leads to the CBD) to “orbital” thinking. The Suburban Rail Loop is designed to connect suburbs directly to one another – Cheltenham to Box Hill to Melbourne Airport – without forcing people to travel into the city centre first.

The lesson: Infrastructure is destiny. When you build a rail loop, you aren’t just moving trains; you are creating new centres of gravity. You are changing the mental map of the city, making “far away” suburbs feel connected and viable for new housing and jobs.

5. Responsible government means thinking beyond the election cycle

Perhaps the most poignant takeaway was the discussion on long-termism. In a political cycle that lasts three or four years, it is politically dangerous to commit to projects that take decades to finish.

Harriet Shing highlighted the Melbourne sewer network and the original City Loop as examples of projects that were not built for the people of that day, but for the millions who would come after. She noted that the original City Loop engineers used hand-operated machinery for the underground network – a stark contrast to the massive tunnel boring machines used today.

The decisions being made now – whether it is the Suburban Rail Loop or the housing targets for the 2050s – are about ensuring that our grandchildren don’t look back and ask why we did nothing when we saw the population growth coming.

The lesson: True city-building is an act of faith in the future. As the Minister put it, “The best time to have done this work is a hundred years ago, but we are where we are”. We must plant trees under whose shade we do not expect to sit.

It has been a huge week of insights. Whether you are looking at the spreadsheet of a Polish business park or the cabinet papers of the Victorian government, the core truth remains the same: building a city is a constant negotiation between the past we inherited and the future we need to build. If you haven’t tuned in yet, make sure you listen to Episode 393R for the economic deep dive and Episode 394 for the full interview with Minister Harriet Shing.

Next time you see a planning notice in your neighbourhood, look at it with fresh eyes. Ask the hard questions: is demolition truly the only option, or is it just the easiest one? When you engage with your local representatives, demand to know if their decisions will stand up in 50 years, not just until the next election.

Next week we are investigating the car-free cities with Lior Steinberg!

Share your thoughts – I’m at wtf4cities@gmail.com or @WTF4Cities on Twitter/X.

Subscribe to the What is The Future for Cities? podcast for more insights, and let’s keep exploring what’s next for our cities.

Leave a comment